The Force Science Institute (FSI) just published a detailed study through the Law Enforcement Executive Forum on the benefits of the passenger side approach when conducting vehicle stops. The authors here at BlueSheepDog (BSD) have long been preaching the tactical benefits of this approach from our own experiences, and we are very excited to see a scientific study supporting this critical skill.

Vehicle stops have often been labelled “routine” police work by the media and those not in law enforcement. Law enforcement officers have often strongly opposed this description recognizing the inherent dangers of this duty. However, the BSD Crew recognize truth in both positions. When examined together (routine, and dangerous) a proper context can be established to understand this vital duty more completely. We’ll discuss this issue at the end of the article.

Force Science Institute Officer Car Stop Positioning Study

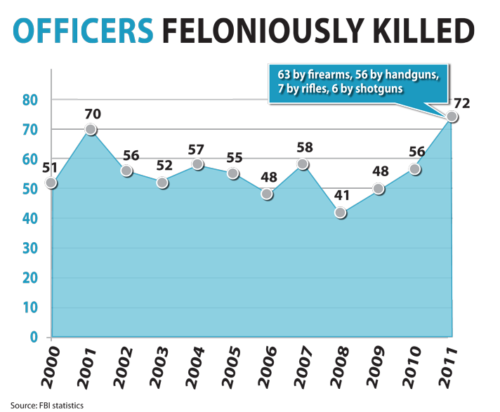

The Force Science study examined thousands of vehicle stop encounters. Recognizing the FBI study of the roughly 10 years from 2001 to 2010, it was determined that 60 of the 541 officer feloniously murdered had been killed during a vehicle stop. In that same time period over 55,000 officers had been injured during a vehicle stop.

A large part of the Force Science study emphasizes the position an officer takes when approaching and standing next to the violator vehicle. The FSI study recognizes that most police academies and agencies recommend the B-pillar position, with minor adaptations on how the officer stands at the B-pillar. There are some valuable reasons for this position (next to the pillar behind the front door). Here are just a few:

- Allows officer to see lunging area of vehicle interior upon approach

- May allow officer to see driver’s hands in side mirror

- Requires the driver to awkwardly look over their shoulder to see the officer

- Otherwise requires the driver to reposition themselves to view officer

- Provides a visual obstruction (pillar) to the officer

- Allows officer to control driver opening the door

- Provides some (minimal) cover if shots come out of the vehicle.

In 2001 Charles Remsberg (author of the acclaimed Street Survival book series) evaluated the driver-side approach position on a suspect vehicle to determine crisis zones – or areas where the officer is susceptible to a firearms attack from the driver. FSI used this information to determine there is only a 10-degree mitigation zone (MZ) angling backwards away from the driver’s door from the B-pillar upon approach from the rear.

If you have not read the Street Survival series, you are doing yourself a serious disfavor. Though somewhat dated now (pictures), many of the principles still hold true – especially in Tactics for Criminal Patrol, and the Tactical Edge.

In other words, the officer has only a 10-degree area where their ability to see the actions of the driver should provide them enough time to react to avoid a successful attack. This is extremely narrow, and should emphasize the need for officers to be students of their art, and understand the science that will keep them safe. Approaching at just a slightly wider angle begins an increasing opportunity for the driver to successfully attack them.

The scenario was highly controlled to meet scientific requirements. Each officer was briefed they would be conducted a vehicle stop on a speeder that would escalate. Nothing about how the escalation would occur, or to what level, was provided. Officers were provided with Simunition pistols and magazines, and were given appropriate eye and ear protection. In addition, a wrist heart-rate band was included to measure peak heart rate spikes from a surprise encounter. The officers were instructed to take one of the following positions on the driver’s side, with taped lines on the floor:

- 180-degrees behind B-pillar

- 90-degrees out from B-pillar

- 45-degrees in front of B-pillar

- 180-degrees in front of B-pillar.

The participating officers were not instructed on the true nature of the study – reaction to a firearm presentation by the driver. In the first 2 scenarios, each officer was confronted by someone claiming to be a Sovereign Citizen who did not recognize their authority and generally would not answer questions or provide required documentation (other than fake papers). Nothing more threatening occurred, and the scenarios were ended after 45 seconds.

However, in the third mock car stop the driver presented a pistol and began firing at the officers after the first exchanges of the Sovereign Citizen arguments. The study measured the time it took the attacker to present and fire the pistol, the time officers took to react to the threat, the time for officers to reach the pre-determined mitigation zone (MZ), and the time for the officers to return fire on the suspect.

Highlights of the FSI Study – Driver Side Approach

Like many Force Science Institute (FSI) studies, this one has incredibly far-reaching implications. Though the study only consisted of 93 officers, with an average experience level of 12.4 years, the reactions and results were close enough to garner a far greater determination of actual officer performance in similar situations.

The results of the driver’s side approach indicated the following average times:

- Suspect presents their firearm – 0.34 seconds

- Suspect first fires their handgun – 0.53 seconds

- Officer’s reaction to the threat – 0.37 seconds

- Officer drawing and presenting their sidearm – 1.95 seconds

- Officer reaching a mitigation zone (MZ) – 2.12 seconds

- First shot from officer’s sidearm – 2.17 seconds.

Interestingly, 12 officers attempted to neutralize the suspect’s firearm at their B-pillar position, but only 3 were successful! Perhaps even more important was the difference in time from officers who reached the (MZ) before drawing their sidearm, and those who attempted to draw their sidearm while moving towards or before moving towards the (MZ). Officers who retreated to safety were nearly 1/2 second faster at presenting their firearm on target, than those who attempted to draw before reaching the relative safety of the (MZ).

Officers should be keenly aware of this, and realize that trying to multi-task in a tight quarters deadly threat (retreating, drawing, attempting to defeat suspect’s firearm) are much slower getting to safety, AND returning fire than those who simply “GET OFF THE X“. This study shows it is wiser for an officer to move to safety than to try to counter the deadly actions of the suspect. This plays right into the understanding of the OODA Loop – where the suspect is at Action and the officer is at the beginning with Observe. Action is always faster than reaction, and a reaction (trying to draw, while moving, under stress) with several complicated parts is even slower. Simply “Get off the X” and then address the threat with your own deadly force.

Of the four different identified positions an officer could assume during the contact, it was surprising to see that each had about an equal number of officers choosing that position. This means about 20% chose the A-pillar position, and 20% chose the 45-degree in front of the B-pillar position. Neither of these positions are ideal, and do not offer as much reactionary gap and “cover” in the event of an attack. Both of these positions were the slowest for firing their sidearm. The A-pillar may be appropriate (briefly) to view a driver reaching into a center console, but we recommend a B-pillar stance at the 90 or 180-degree behind position once that action is complete.

The interesting note on the driver’s side approach from this study is found with the 45-degree and 180-degree were the fastest at drawing their sidearm, but the slowest at firing. This is could be due to the overwhelming sensory overload. The officer sees the firearm and draws their own, but then is in the conundrum of whether to block the suspect’s firearm, flee the suspect’s firearm, or shoot. I believe their exposure at the forward positions leaves them feeling more vunerable and having to decide on whether to “fight or flight”.

Benefits of the Passenger Side Approach

The passenger side approach has been taught to officers for decades, but it is still the least used method when officers interact with drivers on a stop. Though not based upon a scientific study, I believe this is due to officer complacency. The complacency comes from the fact the majority of our stops involve mostly law-abiding citizens who have violated a traffic law. In those situations it is easier and more efficient to simply make contact on the driver’s side.

However, when officers conduct stops on busy roadways or highways, or when they expect trouble from the vehicle occupants, the use of the passenger side approach has proven to be highly effective at reducing risk to officers. We must remember threats to officers are not only from the vehicle’s occupants, but can come in the form of a 3000 lb. moving vehicle as well.

In regards to the passenger-side approach to vehicles where the occupants may be a threat, there are many examples of how the officer survived a deadly attack, or was able to identify a deadly threat prior to the occupants realizing the officer’s presence. BSD did a review of the Officer Leighty incident in Ohio, and his heroic engagement of an armed robber (unknown to Leighty) committed to killing the officer. The video is below.

In this video Officer Leighty used the passenger side approach and it saved his life. The offender/driver can be seen looking back through his open driver’s window, expecting to find the officer approaching from the driver’s side. What Officer Leighty did not know was the driver and his passenger had been on a spree of armed robberies, and were likely high on controlled substances. The driver had a concealed handgun waiting to murder the officer.

When Officer Leighty presented himself on the passenger side he was able to observe the threat, draw his sidearm, and surprise the driver instead of the other way around. In the next few tense seconds Officer Leighty was able to fire on the driver who presented his handgun, “Get off the X” and totally surprise the driver again when he engaged him with more gunfire from the front of the car instead of the passenger door where the driver expected him to be.

This video is one of the most powerful testimonies of the passenger side approach, and should be a clear lesson to all officers on the benefits of this tactic. The advantages may not be as profound as the Officer Leighty incident. On one of my stops I had observed a car load of teens toking it up with their marijuana pipes as they pulled out of a popular gas station. When I stopped the car, and conducted a passenger side approach, each one was looking to the driver’s side. I had about 20-30 seconds of uninterrupted view of the passenger compartment, including observing passengers trying to hide bags of marijuana and pipes. When I finally tapped on the window, the surprise and shock was complete. So much, that when I told the occupants to deliver their “goods” they didn’t even put up an argument.

Highlights of the FSI Study – Passenger Side Approach

The FSI study revealed the passenger side approach provided officers and additional 1/2 second advantage to getting to the safety of the (MZ). The extreme angle, and interior obstructions, made it very difficult for the driver to engage the officer in gunfire, while allowing the officer much more time to inflict hits on the driver.

The (MZ) on the passenger side approach also increased to 45-degrees, from the tiny 10-degree angle on the driver’s side approach. This means officers on the passenger side have a much wider area of movement, and distance from the stopped vehicle, while still being able to reach the (MZ) and avoid shots from the driver.

One of the main reasons for the larger advantages of the passenger side approach is the increase visibility into the passenger compartment. In particular, the officer will gain a much greater view of the driver’s right side, and lap, than when approaching on the driver’s side. Since roughly 90% of humans are right-handed, approaching a vehicle where the officer can obtain a better view of the driver’s right hand is statistically more sound than approaching blind on the driver’s side.

On driver’s side approaches, the passenger compartment quickly becomes obscured once the officer passes the rear bumper. Seat backs, head rests, and the structure of the roof all tend to reduce visibility on the driver. This is one of the main reasons officers are taught to take such an extreme angle back from the B-pillar. It is recognized the officer will be at a disadvantage looking in on the driver, requiring being further back to provide greater reaction time.

On the other hand, when approaching from the passenger side, the blockage from the head rest, seat back, and vehicle actually begins to diminish the closer the officer gets to the B-pillar (passenger side). The passenger compartment, particularly around the driver actually opens up for the officer’s view. Although the right-handed driver may have an easier movement to their right (rather than crossing their body to the left), they still must overcome obstructions within the car to get a good shot at the officer. On the driver’s side approach the body mechanics of the driver are more difficult, but the obstructions stop once the driver reaches the window.

FSI Study – Fastest to Mitigation Zone (MZ)

It is not surprising officers approaching on the passenger side reached the (MZ) nearly 1/2 second faster than any of the driver’s side approach techniques. Officers have a much greater view of the driver, and the presentation of a firearm from a concealed position around the driver. The slowest times to the (MZ) where the officers at the A-pillar, or 180-degrees in front of the B-pillar. The second fastest to the (MZ) were officers at the 180-degree behind the B-pillar position.

Even in the video below, the Texas DPS Trooper conducts a passenger side approach, and when he is attacked he is able to flee first (to avoid being shot) and then return fire effectively (striking down two of the assailants).

The dilemma of an officer’s decision-making cannot be understated here. When further exposed (forward positions) the officer is likely feeling much more compelled to do something to intervene, rather than retreat to safety. This is particularly true when an officer knows they must travel the entire distance of the driver’s window before even beginning their travel to the (MZ) had they been at the B-pillar.

FSI Study – Fastest Officer Firearm Presentation

On the other hand, the officers that were at the A-pillar, or 180-degrees in front of the B-pillar, were the fastest to present their sidearm. This may very well be due to the officer having a greater view of the driver’s actions, and being able to recognize a threat slightly quicker.

However, before someone jumps on the A-pillar parade, we must also recognize this slight edge in presentation time is still slower than the suspect’s presentation time. In addition, it is very likely the presentation time at the A-pillar is slightly faster than the other positions because the officer (being exposed) feels the only viable option is to shoot it out. Retreat to the (MZ) drops on the option list, because the officer has already bitten off so much space to the driver/suspect that retreat to safety is much less likely to succeed without being hit.

Finally, though the presentation time is slightly faster at the A-pillar, the surprising research shows officer weapon presentation being nearly identical for each position studied. The differences are literally 1/10th or 1/5th of a second, between all of the positions. Those who take the A-pillar stance may believe it gives them the best view of the driver, but it doesn’t appear to make them faster in presenting their firearm upon a threat.

FSI Study – Fastest Officer Firearm Discharge

Somewhat surprisingly, the fastest officer sidearm discharge times happened from officers who were originally at the 45-degree angle forward of the B-pillar. Again, I believe this is due to officers feeling compelled to immediately meet the deadly threat with deadly force, because they have bit off too much space and feel exposed.

Officers who stood at the A-pillar were second fastest, only about 0.1 second behind, while officers on the passenger side were only 0.2 second behind the 45-degree forward officers.

The slowest officers to discharge their sidearms were originally at the 180-degree behind the B-pillar position. This appears to confirm my hypothesis that officers who feel exposed from their forward positioning tend to try to fight it out first (before seeking cover), while officers who have some advantage of cover (passenger side, 180-degree behind B-pillar) seek the safety of the (MZ) first and are successful most of the time.

“Routine” Vehicle Stops

Earlier in the article I mentioned the argument between whether car stops are “routine” or should be labelled as something different or “dangerous. I believe a combination of the sides is appropriate and I lay out my arguments below.

First, a vehicle stop is something performed so often by police officers (likely on a daily basis) that the action can easily be placed in the commonly performed duties. As such, vehicle stops can be considered “routine” duties of a police officer. Meaning a vehicle stop is something commonly performed by an officer on a regular basis. Other “routine” duties of an officer are things like taking reports, patrolling high crime areas, and answering calls for service. This doesn’t make these events less dangerous to call them “routine”, it just recognizes they are activities commonly, and frequently performed by officers.

In contrast, an officer may only take someone with mental illness into protective custody once or twice a month. Officers may only be required to respond to an armed robbery or armed barricaded subject call once every 3-4 months. Even though these actions are extremely dangerous, they are not “routine” because they lack the frequency of car stops or responding to other more frequent calls.

The BSD Crew does not desire to minimize the risks associated with vehicle stops, however we recognize the frequency with which those duties are performed can place this dangerous activity into a “routine” category. In fact, we believe that if our readers were to examine their own experiences with car stops they would likely discover similar results as we have found:

- Vehicle stops occur on a daily basis, often more than one per shift

- High risk (felony) car stops are rare, perhaps only a few times per year

- Attacks from vehicle stops are even more rare, perhaps once a year or less.

- Attacks during vehicle stops are often fast and violent.

This attack was after a stop, but in the ensuing pursuit and crash, the driver/shooter is able to exit and fire on officers in less than two seconds. Thankfully the original officer had called for back-up and that officer was able to dispatch this murderer to where he belongs.

Final Thoughts

The BSD Crew highly recommend that officers read the FSI study in its entirety and more than once. Not only for yourself, but share the life-saving information with fellow officers, commanders, and training officers. When literally fractions of a second decide life and death, officers should know the facts, and be able to make the most informed decision available to them.

What is clear from this study is officers are by far (1/2 second) safest when using the passenger side approach. A half second may not seem like much, but trained shooters can fire several shots in that time. Also clear is officers choosing to make a driver’s side approach are fastest to the (MZ) when standing behind or at the B-pillar. Retreat may seem cowardly, but in the right circumstances a tactical withdraw is not only wise but prudent as well.

Force Science Institute has been one of the strongest supporters of law enforcement in recent history. Using scientific principles and studies, FSI has shown the human mind and body can only perceive threats in a delayed manner from the actual threat (action is always faster than reaction). In addition, the human mind may instruct the body to continue to respond in a certain way even when the threat itself has changed – for instance, continuing to shoot after the suspect has turned away. The brain is fast, but it must still process hundreds if not thousands of bits of information in fractions of a second. This requires time, and time is not always on our side.

This study on the passenger side approach is right in line with what we have been teaching for many years, and we are glad to see the science behind the art. If you are not a frequent site reader of FSI you should be. You wouldn’t think about hitting the streets without your duty belt, and you shouldn’t think about hitting the streets without the understanding of the science behind how we do our duty.

GJNM says

Excellent article and good work by FSI as usual. I’m a detective but I work a lot of uniformed traffic OT and reading this was sobering for me. I’ve always favored a driver’s side approach prior to this but I’ll be using the passenger side approach a lot more. The only downside is that detecting impaired drivers is harder from the passenger side; small price to pay for increased officer safety though.

Aaron E says

I admit I tend to favor the driver’s side approach as well, especially since I’ve move to a day shift. I was still doing passenger side approaches on highways and other busy streets. However, I plan on doing more passenger side approaches in the future.

Duane K says

I try to go to both windows, initially on the passenger side, then when returning after running the drivers info on the driver’s side for this exact reason. I can’t count the number of times I observed some form of p.c. I would have otherwise missed going only on one side. Additionally, it repeats the surprise since the subject typically assumes you’ll be returning to the same window.

TM says

I performed passenger side approaches whenever possible. I would exit my patrol car, walk around the BACK of my patrol car – while watching the violator – and walk along the passenger side of my patrol car, carefully approaching the violators passenger side window. Oftentimes I stood at the violators rear window and directed them to open that window, if tinted, before I crossed in front of it.

I always found drivers looking for my approach in their exterior driver side rear view mirror and never seeing me….even in broad daylight.

It was even better at night because walking behind my patrol car ensured I would never cross the beam of my spotlight and tip them off to my location.

The other advantage of approaching the violator after walking behind my patrol car, was that the violator always thought I exited from the passenger side of the patrol car. They believed ‘my partner’, ‘the driver’, was still watching from a distance. I would reinforce that illusion by asking the violator if they “knew why WE stopped you”….even though I almost never had a partner riding shotgun with me.

I also found it easier to detect alcohol or marijuana odors. Violators normally opened their driver side window as I approached. They then would have to open the passenger side window. Usually enough of a breeze would come through the vehicle and carry any odors out…. especially as vehicles went by and stirred up air currents.

Aaron E says

Excellent points TM. When I worked nights I did about 50-50 on my approaches. There was more than one time I was able to observe evidence of a crime before the occupants even knew I was there. I’ve moved to a day shift and have slipped back to doing more driver’s side approaches. With the safety factors pointed out in the FSI study I plan on doing more passenger side approaches.

TM says

I spent 20 of my 21 year career on day shift, since I was also a CSI, Speed Measurement instructor, handled the evidence room and processed abandoned vehicles.

I can’t tell you how many people I literally startled by approaching on the passenger side, watching them look for me and then jump when I said ‘hello’!

I also watched as they searched in their purse or glove box, unbeknownst to my presence.

There were even times when I heard brief conversations as they tried to formulate a story together.

Ben H. says

Started my LE career in 1997 and was taught from the beginning to always make driver’s side approaches while in the Police Academy. It wasn’t until a couple years later I was introduced to the passenger side approach. It was an awkward tactic when I began to use it because it was new and if you have been policing long enough you know how new things sit with Cops…Little did I know that this awkward traffic stop tactic would one day save my life. Five years into my LE career I conducted a traffic stop for an improper headlight violation. Prior to this shift date I was training a new Officer who subsequently completed his training and moved on to another FTO the day before so I was riding solo for the first time in 12 weeks. For whatever reason, I like to think the Man Above was looking out for me, I made a passenger side approach on the violator vehicle. I observed only one occupant in the vehicle seated behind the steering wheel. As I approached I noticed the driver already had his hands on the steering wheel and appeared to be searching for me in his side mirror. When I got to the trunk I touched the vehicle with my left hand and proceeded to take another couple steps forward to contact the driver. Midways of my second step I surveyed the rear section of the vehicle and to my surprise I observed a second subject laying in the back floorboard. The subject was lying on his back and his feet were against the rear driver’s side door. He had a double-barrel shotgun in his hands which he was pointing at the rear drivers side door. Obviously I immediately drew my weapon, I did not say a word, moved to the passenger door of my vehicle, and called for assistance. Multiple units arrived within seconds and we conducted a felony car stop removing the driver first, securing him, and then ordered the back seat offender from the vehicle. After a very tense few minutes the rear passenger placed his hands in a visible position and exited the vehicle. He was taken into custody without incident. The weapon was recovered and it was found to have been loaded with 2 2 & 3/4 inch 00 buckshot which would have turned my day into a very bad one. Driver had multiple warrants with our agency for minor violations and had a lengthy non-violent criminal history. His accomplice was found to also have multiple warrants with my agency and was also wanted from another agency on multiple counts of armed robbery and upon conviction he would have been sentenced to life. I survived this encounter without any shots being fired. I was very lucky that day and very fortunate as well. I give all the thanks to an Alabama State Trooper who introduced me to the passenger side approach. He unknowingly taught me something that ultimately saved my life. I use the PSA on all traffic stops I make now and have done so for many years despite the level of discomfort it may present to me. I teach this tactic to all the new Officers I am asked to train and always tell them this story in hopes that this tactic will save their lives, as it did mine, during their LE career. This was a great read and I will be inserting this into my training itinerary moving forward. Stay safe brothers…

Aaron E says

WOW! What an excellent example of the benefits of the passenger side approach Ben. No doubt this tactic saved your life and helped bring two very bad criminals to justice. Even though the driver may have only had minor offenses, his compliance in the shotgun holder’s actions crossed the line for him as well.

We started the job in the same year, and I have an Alabama connection. My father was raised in Brewton where my grandmother lived for years. I also graduated from Auburn with my CJ degree. Stay safe and keep preaching the passenger side approach.